This is the first in a series of articles this January aimed at rethinking what cinemas could be when we can restart them. I’m leading a discussion on accountability for cinema workers with London Short Film Festival on 23 January (this Saturday) too, which is part of the same thinking about what should change. You should come to that if you are a front of house worker or responsible for their work. It’s free to attend.

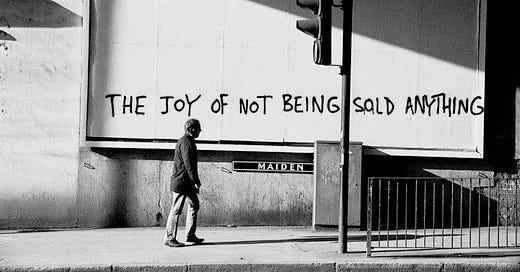

Imagine if you will, your beautiful cinema façade. Glowing lights, beckoning you in for experiences that reshape your life, where you can sharing uncharted experiences, feeling waves of resonance with strangers through some near mystical process. Now imagine, above your charming branding, a larger neon sign, ‘BROUGHT TO YOU BY DR. PEPPER.’ An unthinkable betrayal of who you are and your values? A hideous distraction to your core mission of sharing film art and serving your community? Unthinkable, no? And yet, at almost every cinema in the UK, we hand over an even more protected space than the outside of the building. I speak of the thirty minute endless march of screen advertising.

Screen advertising has a powerful effect on audiences. It’s tempting to think it’s all just filler, something to empty your popcorn to, chat to your friend through or arrive late because of. There’s some terrific research by DCM (the UK’s largest screen media agency, owned jointly by Cineworld and Odeon and providing an enviable revenue stream for their estate and beyond) that says quite the contrary. Spending on cinema advertising – in a landscape where print and other non-digital spending is in decline – rose 14% through DCM in 2019, a healthy bump on what was a steady upward trend. Advertisers know the cinema is set apart. Cinema is a unique opportunity to sell because of all the reasons we love it: it’s a special – maybe even sacred – space where people create memories, have strong emotions and offers that rarest of modern commodities: attention.

Yet all of the reasons that cinema appeals to advertisers should be anathema to cultural cinemas. There is so much about the philosophy of independent cinemas that is belied by showing screen advertising. Multiplexes thrive on a ‘let the market decide’ programming agnostic principle. If it’s legal to show, isn’t likely to cause complaints and stands to make a few quid, they’ll show it. Independent cinemas aspire to a level of trust and care with what they put on screen. At their most high-minded, they stand closer to the museum than the multiplex, less Vue and more V&A.

Arts organisations (especially film festivals) fret about allowing a sponsor to benefit from the credibility they have with the audience. Yet when it comes to screen advertising, cinemas delegate that trust – that opportunity to speak to their audience before the filmmaker does – to media sales companies whose business is in attracting the highest paying company, not the one that matches your principles.

Showing ads in a cinema makes less and less sense in today’s media landscape. While consumers are used to advertising with their content, the norm today is that paying a premium rids you from being advertised to. When you support a podcast or pay for Spotify’s Premium tier, you’re removing yourself from being the product sold to advertisers and supporting them directly. Facebook, online newspapers or 4OD rely on gathering as many eyeballs as possible to sell to advertisers. In the modern consumer’s mind, there are very few spaces that match paying a premium (e.g. a cinema ticket) with also being sold to (cinema advertising). Putting it bluntly, it’s like buying an audiobook with an unskippable five minute spiel about Popchips preceding it.

If this feels rather high-minded, then consider it purely on the basis of market differentiation. You don’t even need to particularly object to what’s being what’s advertised on screen; it’s just not what audiences have come to you to see. Independent cinemas pride themselves on being cultural spaces (and rely on funding streams that position them as such). Not showing ads could become a hallmark of independent cinemas, an associative link of respect for audiences. Even if audiences don’t clue in to the deeper philosophy, they will likely just be relieved by not having to sit through adverts. It’s a bonus and something audiences will seek you out for (especially when you have programming crossover with the multiplex).

There’s also a raft of operational reasons to ditch ads. Over the last few years, cinemas have pushed towards an ‘infrequent but expensive visits’ audience model, pushed by certain ‘must see’ titles rather than more frequent attendance to a broader range of films. One thing that stops more regular attendance is the low turnover of ads. Anyone who was a frequent moviegoer in the ‘90s and ‘00s will recall the exquisite torture of sitting through the umpteenth viewing of Diet Coke’s ‘Grandma’s run off with Derek from the bridge club’ ad. Besides repetition, for consumers it bloats an evening at the cinema, edging out those who prefer an early night or to avoid late travel with another thirty minutes to their night. There’s also a beautiful clarity in timings without adverts, ending the ‘What time is the film on?’ box office query (to answer to which becomes ‘More or less the time on the ticket’). While not necessarily enough to add in an extra screening, it’s more likely that people will be inclined to spend time in your bar if they aren’t in a zone of uncertainty about when the actual bit they came for is going to start. I’ve also heard of the frankly baffling move to cut trailers in order to fit in an ever-swelling ad reel. This is utterly counterproductive (both for advertisers and operators) when you consider that research shows that trailers are one of the most powerful tools to encourage repeat attendance. If advertisers really care about eyeballs, then surely they’d like to see more of them on their next ad? Finally, with audience behaviour one of the biggest issues for regular cinema goers (and often pushing people to choose home viewing), why create a situation in which talking and checking your phone are almost necessities to get through the ad reel? Cinema screens aren’t chapels or crypts, but setting an agenda of shared concentration and respect for what’s shown isn’t helped by running ads.

Okay, so you’ve heard the problem, but I know the rebuttal: it’s free money. Consumers have mostly accepted it, it’s a steady fixed revenue in a volatile and unpredictable marketplace and you’ve got a contract. All perfectly reasonable, especially staring down the barrel of another recession, when audiences have spent a year indoors getting cosy with home viewing options and losing expendable income.

But reopening cinemas gives us a chance to reset assumptions about how they can run. The cinemas that have thrived and had their community rally round them over the pandemic months are those that have a clear ethos and connection to their audience. Why can’t resisting advertising be an avowed part of your brand? I remember the breaking point for me on screen advertising was the first time I visited BFI Southbank and saw they’d introduced a gold tier advertising placement (that’s the one that plays immediately before the feature and costs a premium because you’ve got the most viewers and the highest prestige). I’ve been a BFI member for over fifteen years, and I felt like it was the breaking of a covenant. The BFI expends a lot of energy reminding us it’s a charity and values film, both of which feel deeply out of step with advertising on screen. What if this situation was reversed?

Respecting your audience and being transparent builds trust and understanding. Why should members of the public support you if your image is one of a commercial organisation? Advertising for yourself (for the work you do, for your membership, for your upcoming seasons and programming, hell, even for your concessions) has much less impact if it’s vying with every other advertiser who paid for access to your cinema.

Another alternative is taking the work of cinema advertising in house. Cinemas used to be full of cheap and cheerful static slides touting local curry houses and taxi services. While there’s a burden of staff time in managing and creating ads, there’s an opportunity to be in control of who gets access to your audience. What if your cinema advertising became a powerful quid pro quo with local businesses? When you consider the value of screen advertising and how targeted it is to local populations, either as cash or in-kind, you have a powerful tool. Your cinema advertising could be a place to show who you are and who you stand for, from local good causes, to local businesses. Could there even be a place for the return of the ‘programme’, with shorts from local filmmakers? The power of independent cinemas comes from a unique, people-centred approach. Why do we abandon that with what’s shown before our films?

If these substitutes don’t feel possible, how about ringfencing your ad revenue every year towards particular projects, ones that you’re unable to find a funder for or pay for from revenue but that speak to your core mission?

Perhaps asking for this to change is barking up the wrong tree at the wrong time, but I’m very happy to demand the impossible at the moment. We accept so much in the service of capital. Is it too much to ask that we have spaces where they can’t reach?